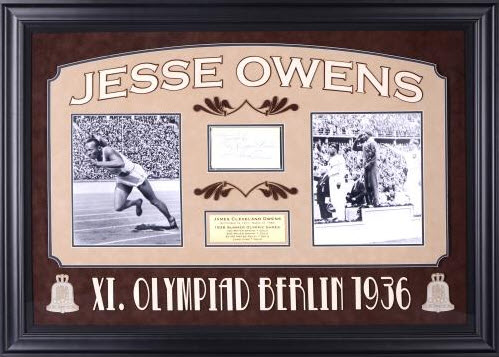

Jesse Owens won his fourth gold medal at the 1936 Olympics on August 9, 1936. He ran the first leg for the U.S. team in the 4×100 meter relay. Prior to his participation on the relay team, Owens was already “the big story” of the 1936 Olympics (at least among the athletes), having won the the long jump, as well as the 100 and 200 meter individual sprints.

Click here

As if there wasn’t enough controversy surrounding the 1936 Olympics, Owens and his relay teammate Frank Metcalfe (They were among the 18 African American athletes that Hitler referred to as America’s Black Auxiliaries.) were named at the last minute as replacements for two Jewish sprinters, Marty Glickman and Sam Stoller. Until a day before the race, it was assumed that the relay team would be comprised of Glickman, Stoller, Frank Wykoff and Foy Draper. Owens and Metcalfe hadn’t even been involved in any baton passing practices. U.S. track coach Lawson Robertson claimed that he feared that the Germans were hiding their best sprinters in order to upset the U.S. in the relay, and that he had to use Owens and Metcalfe in the race. Owens and Metcalfe had in fact, run faster times in the 100 meters than Glickman and Stoller. On the other hand, Lawson’s concern about “stealth German sprinters” seems dubious. Even in 1936, world class sprinters did not appear out of thin air. As it turned out, the U.S. team ran away from the field, winning the race by 15 meters. Unless they tripped, with Stoller and Glickman running, the U.S. would have probably still won, although perhaps with a smaller lead at the finish.

Marty Glickman speaking about his experience.

I was always aware of the fact that I am a Jew, never unaware of it, under virtually all circumstances. Even in the high school competitions, and certainly at college and for the Olympic team, I wanted to show that a Jew could do just as well as any other individual no matter what his race, creed, or color, and perhaps even better.

The Olympic stadium itself is a very impressive place. It was particularly impressive then, filled with 120,000 people. When Hitler walked into the Stadium, stands would rise, and you’d hear it in unison, “Sieg Heil, Sieg Heil,” all together, this huge sound reverberating through the stadium.

Everyone seemed to be in uniform. As for banners and flags, they were all over the place, dominated by the swastika. The swastika was all over. On virtually every other banner we saw, there was a swastika. But this was 1936, this was before we really got to know what the swastika truly meant.

There was antisemitism in Germany. I knew that. And there was antisemitism in America. In New York City, I was also aware of the fact that there were certain places I was not welcome. You went into a hotel, for example, and you’d see a small sign where you registered which read “Restricted clientele,” which meant, in effect, no Jews or Blacks allowed.

The event I was supposed to run, the 400-meter relay, was one of the last events in the track and field program. The morning of the day we were supposed to run in the trial heats, we were called into a meeting, the 7 sprinters were, along with Dean Cromwell, the assistant track coach, and Lawson Robertson, the head track coach. Robertson announced to the 7 of us that he had heard very strong rumors that the Germans were saving their best sprinters, hiding them, to upset the American team in the 400-meter relay. Consequently, Sam Stoller and I were to be replaced by Jesse Owens and Ralph Metcalfe.

We were shocked. Sam was completely stunned. He didn’t say a word in the meeting. I was a brash 18-year-old kid and I said “Coach, you can’t hide world-class sprinters.” At which point, Jesse spoke up and said “Coach, I’ve won my 3 gold medals [the 100, the 200, and the long jump]. I’m tired. I’ve had it. Let Marty and Sam run, they deserve it,” said Jesse. And Cromwell pointed his finger at him and said “You’ll do as you’re told.” And in those days, Black athletes did as they were told, and Jesse was quiet after that.

Watching the final the following day, I see Metcalfe passing runners down the back stretch, he ran the second leg, and [I thought] “that should be me out there. That should be me. That’s me out there.” I as an 18-year-old, just out of my freshman year, I vowed that come 1940 I’d win it all. I’d win the 100, the 200, I’d run on the relay. I was going to be 22 in 1940. I was a good athlete, I knew that, and 4 years hence I was going to be out there again. Of course, 1940 never came. There was a war on. 1944 never came.

Click here to see this and more Jesse Owens Collectibles